A speech pathologist’s role in stroke management can be both in areas of communication and swallowing.

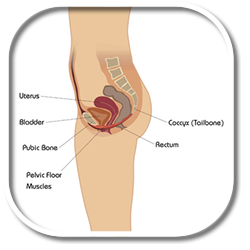

First, starting with swallowing, around 27-50% of all acute stroke patients experience dysphagia or swallowing difficulties. Dysphagia results in decrease in nutrition and hydration, greater risk of aspiration pneumonia, increased length of hospitalization, illness, and in some cases even death.

Speech pathology intervention focuses on assessment, and management of swallowing and eating difficulties following a stroke.

So, when a patient first presents to me, after they’ve had a stroke, I need to establish;

- Are they safe enough to manage oral intake?

- Can the patient actually swallow?

- Can they be deemed safe enough to take their medications orally?

- Do they require, if they do have impaired swallow, modified diet or fluid level?

- Does their diet need to be pureed?

- Do they need thickened fluids?

- If their swallow is so impaired that they cannot manage a diet orally, do they require nutrition and hydration through an alternative means, such as a nasogastric tube?

In those such cases, I need to liaise with the dietician, and refer to their expertise, and collaborate together with them to effectively manage a nasogastric regime.

There is also a role in dysphagia for education of patient, family, and the stroke team in regards to safe swallowing strategies as well as the continuous monitoring and reviewing of the patient, to monitor progress, or also the regression.

A stroke can also affect communication skills, resulting in a disability due to dysphasia, which occurs in a frequency of around 21-38% of all acute strokes, and/or dyspraxia and dysarthria which occur in incidence of 20-30%.

Communication impairment can also be secondary to cognitive problems, such as decreased concentration, attention, increased tiredness, memory, and problem solving deficits. Speech pathology provides specialized assessment, therapy, and advice regarding the best way to help a patient who has a communication problem.

The impact on a patient who does have a communication problem can be a very isolating experience for them. There is a lack of power because they are not able to get their basic needs and wants met because they aren’t able to communicate those. There is anxiety, the patient is also unable to participate fully in the recovery and rehabilitation process. There is also impact upon all allied health nursing and medical staff. There is frustration within staff members because they are unsure in how to engage the patient. There is increased time needed to actually communicate effectively. There’s also the difficulty in building up rapport and developing the whole therapeutic alliance.

So, a speech pathologist works to establish; how is a patient able to express their basic needs and wants? Can the patient actually understand? And then you can establish a basic communication system which allows the patient to participate in recovery, for them to be able to state their wants and needs, be provided with some sort of choice.

Sometimes, if they are unable to speak or express what they want verbally, we can resort to alternative communication systems, such as communication boards.

A speech pathologist’s role also incorporates education again; the provision of information to the patient, the family as well as the stroke team regarding the best suited mode of communication for the patient, as well as ongoing communication therapy for that patient.